Imagine using your favorite productivity app at 30,000 feet — no internet, no loading spinners, no freezes. You keep typing, creating, and editing, and everything just works.

That experience isn’t luck. It’s Local-First architecture.

Your actions are saved instantly on your device. When connectivity returns, everything syncs automatically — without you noticing.

What is Local-First?

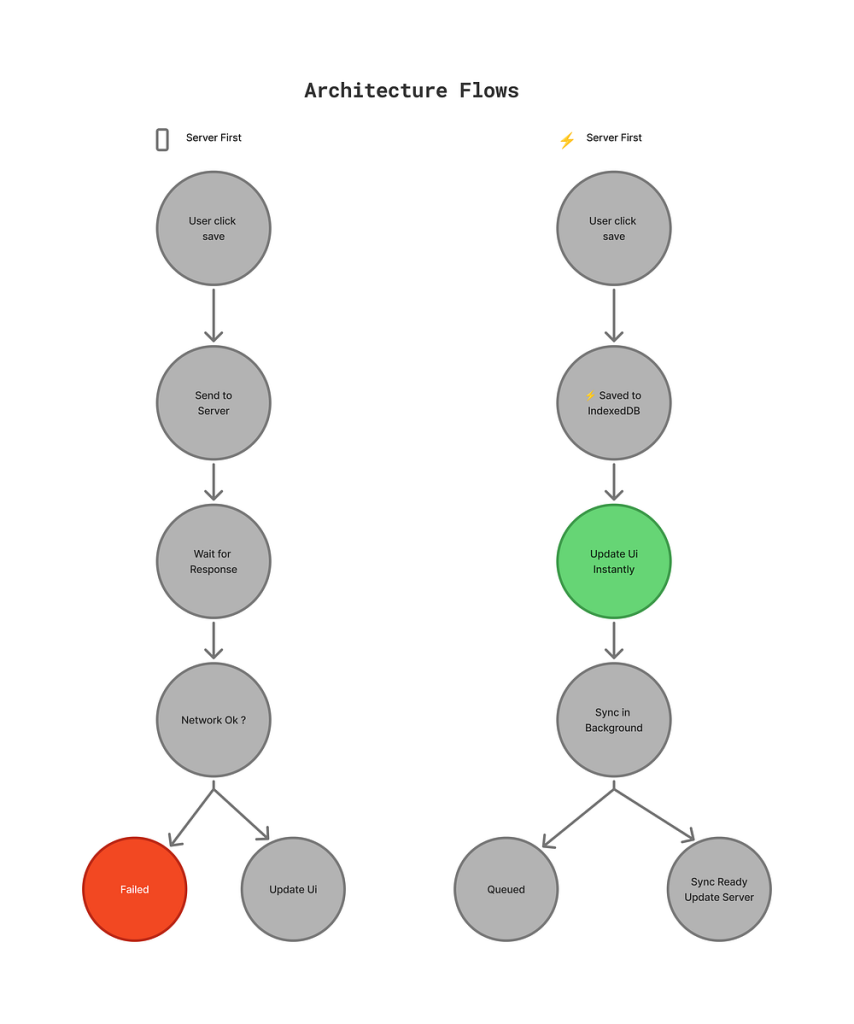

Let’s compare two different worlds.

🌍Scenario 1: Traditional (Server-First) App

You’re building a Notes App:

User types a note → request sent to server → server saves → response returns → UI updates.

If the network is slow or down, the app waits. The user waits. Productivity stops.

🌍Scenario 2: Local-First App

Same notes app, but with Local-First:

- User types a note title → Saves to device’s local database instantly

- UI updates immediately → User is happy

- App quietly syncs to server in the background → User never knows

The Difference: The user feels no delay. The app works offline. When connectivity returns, it syncs automatically.

Simple Definition

Local-First means your app treats the local device (browser’s local database) as the primary source of truth, not the server.

The server is still important — it’s a backup and handles multi-device sync. But the user’s device is the “main source of truth.”

Career Impact (The Secret Nobody Tells You)

Modern users expect apps to work everywhere — on flights, in tunnels, on unstable networks. Traditional apps fail silently in these moments. Local-first apps don’t.

This isn’t experimental architecture. It’s already in production:

- Figma for real-time collaboration

- Linear for instant task creation

- Notion for offline-first editing

Understanding local-first systems is increasingly valuable — because companies care deeply about fast, reliable user experiences.

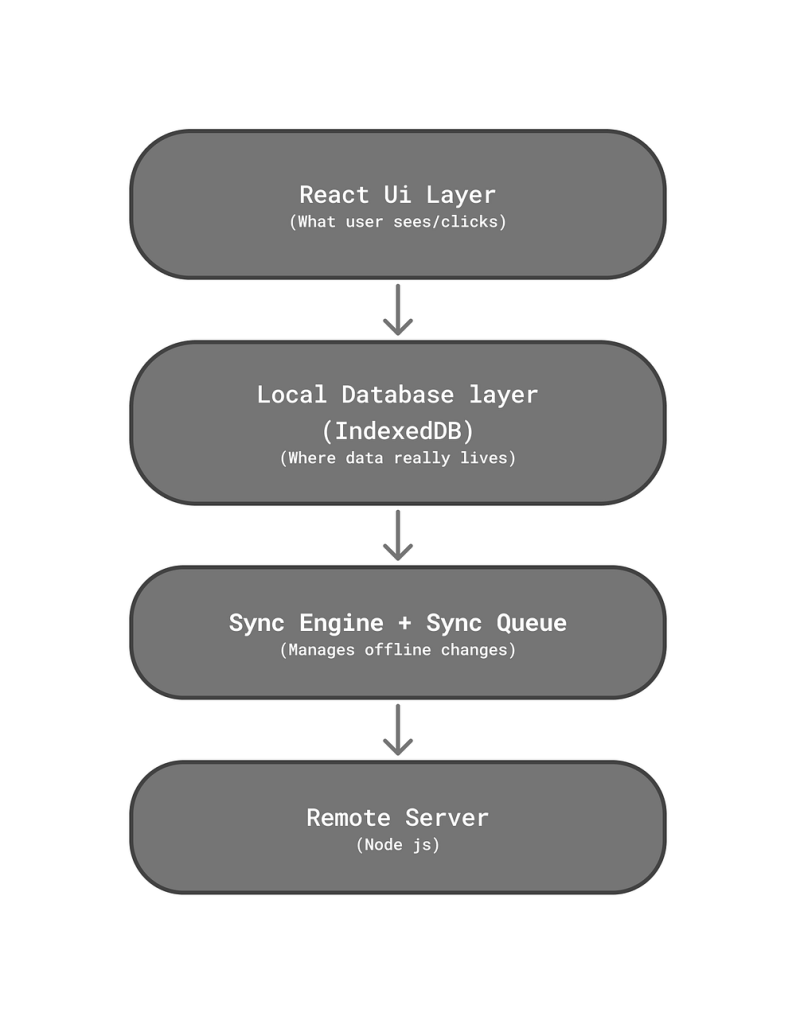

How It Actually Works (The Architecture)

Think of a local-first app like a 4-layer sandwich:

Layer 1: React UI — What users interact with

Layer 2: IndexedDB — Local storage in the browser (up to 50MB+)

Layer 3: Sync Engine — Handles offline changes

Layer 4: Server — Handles cloud sync

The Data Flow

When a user creates a task:

User Action → IndexedDB ← (instant update)

↓

React re-renders ← (instant UI update)

↓

Sync Engine ← (runs in background)

↓

Is app online?

├─ YES → Send to server now

└─ NO → Store in Sync Queue

💡 The first three steps happen instantly.

💡 Step 4 happens whenever the network is ready.

This is why the app feels magically fast.

What is syncQueue?

The syncQueue is what makes offline functionality reliable.

When users act offline, their changes are added to a queue and sent to the server once connectivity returns. Think of it as your app’s courier — it never forgets a delivery, even when the road is blocked.

Imagine you’re offline:

- Add task 1 ✓ (synced = false, added to queue)

- Add task 2 ✓ (synced = false, added to queue)

- Delete task 1 ✓ (action added to queue)

syncQueue looks like:

[

{ action: ‘CREATE’, task: {…}, synced: false },

{ action: ‘CREATE’, task: {…}, synced: false },

{ action: ‘DELETE’, taskId: 1, synced: false }

]

Without a syncQueue:

- Offline changes could disappear

- Deleted data might reappear

- Devices would drift out of syn

syncQueue ensures every offline action is remembered and synced — no data loss, no surprises.

Conflict Resolution in Local-First Apps

In local-first applications, data is saved on the device first and synced later. Conflicts occur when the same data is modified in multiple places before synchronization. Below are the most common conflict-resolution strategies, explained briefly with real-world examples.

1. Last Write Wins (LWW)

What it does:

The most recent update overwrites earlier ones.

Real-life example:

You edit a note on your phone at 10:00 and edit the same note on your laptop at 10:05. When synced, the laptop version replaces the phone version.

if (incoming.updatedAt > current.updatedAt) {

overwrite()

}

Best for: Simple apps where occasional data loss is acceptable.

2. Field-Level Merge

What it does:

Only the conflicting fields are resolved instead of replacing the entire record.

Real-life example:

On one device you update your profile photo, and on another you update your bio. After sync, both changes are preserved.

Best for: Structured data like profiles and settings.

3. Operational Transformation (OT)

What it does:

Stores and merges user actions (operations) rather than final data state.

Real-life example:

Two people typing in the same Google Doc at the same time. Both users’ text appears correctly without overwriting each other.

Best for: Real-time collaborative editors.

4. CRDTs (Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types)

What it does:

Uses special data structures that automatically merge changes without conflicts.

Real-life example:

Offline chat messages sent from multiple devices appear correctly once all devices reconnect.

Best for: Offline-first and multi-device apps where data loss is unacceptable.

5. Manual (User-Driven) Resolution

What it does:

The user decides how to resolve a conflict.

Real-life example:

Git shows a merge conflict and asks the developer to choose which changes to keep.

Best for: Critical data where correctness matters more than convenience.

6. Domain-Specific Rules

What it does:

Conflicts are resolved using business logic.

Real-life example:

In an expense app, a manager’s approval update overrides an employee’s edit.

Best for: Business-critical systems with clear rules.

Key Takeaway

Conflict resolution is a design choice, not just a technical one. The right strategy depends on how critical the data is and what users expect when working offline.

✅ The Good Stuff

1. Lightning-Fast UI

Your users feel like the app responds before they even think.

2. Works Everywhere

Users create, edit, and delete tasks offline without error messages, and everything syncs automatically when connectivity returns.

3. Smooth, Frictionless User Experience

Every interaction gives instant feedback, making the entire experience feel polished.

4. Better Performance at Scale

Your server handles sync, not every click. This means lower hosting costs and better performance even with thousands of users

5. Multi-Device Magic

Edit on your phone, continue on your laptop — everything stays synchronized automatically without special buttons or user intervention

❌ The Tradeoffs

1. Conflict Resolution Complexity

When two devices edit the same task simultaneously, which version wins? This requires thoughtful strategies —This is what we discuss earlier.

2. Data Consistency Challenges

Local and server data can drift apart when devices sync at different times. Your sync engine must reliably merge these states — one device might have stale data while another has fresh updates.

3. Storage Limitations

IndexedDB typically caps at ~50MB per domain. Perfect for tasks and notes, but not for media-heavy applications.

4. Debugging Challenges

User data lives on their device, making it harder to reproduce bugs. You’ll need browser DevTools expertise and remote debugging strategies.

5. Increased Complexity

More code to maintain (local DB + sync engine + conflict handling) means a steeper learning curve. You’re trading simplicity for superior UX.

Final Thoughts

Local-first isn’t just another architecture pattern — it’s a shift in how we think about building software.

Local-first teaches us one powerful idea:

software should be as reliable as the device it runs on.

When your app keeps working offline, in weak signal areas, or in complete network failure, it stops being a tool and becomes something users can rely on — anytime, anywhere.

Great apps earn loyalty not by being always online — but by being always reliable.